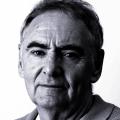

STEPHEN Tompkinson’s face is so familiar you sense you could shave it and be aware of the plooky part or the area that needs that extra squeeze of Nivea in the morning.

In the Eighties he teased his way into our consciousness with regular roles in television dramas such as Chancer and Minder.

But since 1990 when his fake news creation Damien rode in on Drop the Dead Donkey he has been ever-present, playing the incomer priest in Ballykissangel, the big game vet in Wild at Heart and the quirky (aren’t they all?) detective in DCI Banks.

And when not grabbing leading roles in television the actor has captured major theatre leads in the likes of Spamalot and, right now, stage classic Art.

However, that raises the big question: what is there about him that makes him the producers’ choice – and the envy of so many actors?

In his dressing room at the Lowry Theatre in Salford, where minutes before he has been on stage in Art before a near sell-out audience, the actor, from Stockton-on-Tees in County Durham, glistens with stage sweat rather than star sparkle.

He’s wearing a bright red baggy grandad top and baggy bottoms which complement his baggy eyes.

On a good day he could be mistaken for a member of Mumford and Sons, on a bad day, a bloke who spends his days in a small-town bookies before going home to a frozen dinner.

The first clue to his success seems to be he doesn’t regard himself as such.

“No,” he says emphatically, smiling. “I’m now 52 and I’m aware there are far more successful actors in television than me.

“You just have to think of Christopher Eccleston, John Simm, David Morrissey, David Thewlis, Jimmy Nesbitt...”

It’s debatable whether some of those names (Nesbitt apart) are indeed more in demand.

But you sense perhaps part of his ability to convince as a series of believable, likeable ordinary blokes (even his reprehensible Damien had an endearing dishonesty about him) is that the actor has retained an incredible sense of gratitude for what he has been given.

He still references his banker dad and his teacher mum who picked up the bills for the first two years of his stint at drama college in London.

Their investment paid off straight away. Tompkinson won the 1987 Carleton Hobbs Bursary and a contract with BBC radio before he had even left the London School of Speech and Drama.

But he wasn’t blinded by the bright lights of early success. “I started off in radio and did 54 plays in seven months,” he recalls. “It’s still my favourite medium.”

“On radio, you are performing to an audience of one, you are going direct to the listener.”

But you don’t make any money in radio? “You’re right,” he shrugs. “But there are no egos and you get to work with great people.”

So he doesn’t need to be seen by an adoring public? “No,” he says in clipped tone, suggesting no dubiety whatsoever.

Tompkinson says he has never feared failure. This actor’s ego seems contained, but certainly not absent.

“No, that never happened,” he offers, without sounding boastful.

“I was getting supporting roles before I landed Drop The Dead Donkey then the series lifted me on and helped me to be seen for the lead roles.

“And when Ballykissangel came along it [fame, and the show’s success] went through the roof.”

Tompkinson’s heavenly performance as the idiosyncratic priest bled into hooking up with co-star Dervla Kirwin in real life. Given that combination, he could have been him forgiven for assuming ideas above his station. But he explains why this was less than likely.

“Me dad said to me at this point: ‘If people are nice to you, then you be nice back. You can’t take anything for granted’.”

But that’s not to say the TV priest was heading for sainthood. Always a creature who loved to socialise, Tompkinson’s drinking reached a critical point.

Was it about escape? “It was more about exuberance,” he says with a wry smile.

“But you realise you can’t burn the candle at both ends and you don’t want others thinking, ‘I’m pulling my weight and you’re taking the p***’.”

The actor had been married to a radio producer before becoming engaged to Kirwin. He then went on to marry again, which produced daughter Daisy, now 17 and planning to become an actor.

Thirteen years ago he met Foreign Office diplomat Elaine Young in a Glasgow piano bar.

Daisy moved in with the couple and Tompkinson cut out the drinking. And focused on work. Now, he’s storming his way through Yasmina Reza’s Art, which tells the story of three pals of 25 years standing who come together to debate a painting which Serge (Havers ) has bought, reckoned by one to be worth north of £200,000.

The problem is the painting is white. All white. But Marc (Denis Lawson) is appalled at the price tag and the pair go to war. Meanwhile, Ivan (Tompkinson) sits in the middle of his two chums and in the process tells lies as white as his chum’s painting.

“The picture will always polarise the audience, raising the question of what is actually art?” says Tompkinson.

“But it’s really a play about friendship; how honest should one, can one be? What should we really expect from friendship?”

Would he tell the truth in such a situation in real life? “Oh, yes,” he says, laughing.

“I’ll stick to my guns when it comes to things I think I know about.”

He smiles, but his voice is serious. “Take Laurel and Hardy, for example. If you don’t like Laurel and Hardy you can’t be my best friend. There’s something missing in your make-up as far as I’m concerned.”

But if he lends an honesty to his creations, he also brings a real vulnerability, as shown in his festive starring role in Neil Forsyth’s remarkable Eric, Ernie and Me as Eddie Braben. “Landing parts like that is why you get into the business.”

But as chat runs on, another factor in Tompkinson’s success story emerges. Stephen Tompkinson admits he can’t not attempt to be funny.

His acting epiphany in fact came about when watching Laurel and Hardy with his grandad, who told him Laurel was the one to watch.

“You saw a lot of Stan today in the performance of Ivan,” he says. “If I can bring him in anywhere I will. You should always nick from the good ones.”

Stephen Tompkinson is also a grafter, to the point he’s soaked in sweat – in a play featuring three blokes chatting in a gallery.

But there’s another reason for Tompkinson’s continued success. He’s everyman. He’s James Stewart with bags under the eyes.

The actor laughs when asked if he’s happy not to look at all like Ryan Gosling? “Oh, yes,” he says, grinning.

“You don’t get that thing whereby you walk in a bar and half the blokes want to punch your lights out. Instead, I’m the bloke who’s done so many family Sunday night dramas you give people that reassurance they don’t have to worry about reaching for the remote to protect the kids.”

The challenge he says is to keep going, to play believable characters with a sense of mischief about them.

“I love what I do,” he says, beaming. “I love the thought of filling out a theatre in Salford on a Wednesday then coming up to Glasgow with that show.

“I love being an actor. But here’s the thing; I don’t feel I need to play Richard III. And I’ve missed out on Hamlet. So what?”

Art, The Theatre Royal, April 9-14

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here